Imagine I told you,

“Over the past 10 years, you’ve made money in the stock market, but you could have made a lot more. The people managing your money charged you more than average, and had big parties each year. This year the main party was awesome -- a famous comedian performed, the cast of Hamilton, among others -- really great lineup. Don’t worry, you were invited…if you could take off from work and get yourself to New York City for a Friday in November.”

Unfortunately this is not fictional. For shareholders of the Baron Growth Fund it was reality, as highlighted in the Wall Street Journal.

Baron’s conference has more glitz than most, but the core problem is endemic: active managers’ fee structures are often out of step with the value they deliver to their clients…you, the people entrusting them with your money.

This is why there’s a shift from active to passive, and why active management companies are increasingly worried. Typically around ~80% of active managers underperform comparable indices, and the 20% of outperformers are virtually impossible to pick out ahead of time.

I am from the world of active management, having spent 6 of my 10 years at Goldman Sachs as a hedge fund investor. I understand and appreciate the potential merits of active management (markets are not always perfectly efficient), but I also see the shortcomings (the opportunity to outperform does not mean that will actually happen, and the data shows that usually outperformance does not occur).

Let’s take a look at the largest fund managed by the hosts of the party described above, Baron Funds. What does that party really cost you?

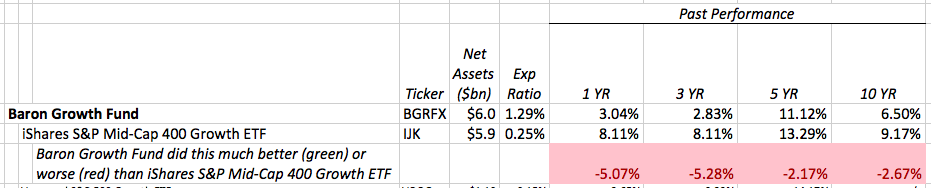

Imagine 10 years ago you’d invested $100,000 in the Baron Growth Fund. As of the date of this analysis, you’d have $187,714, or a 6.5% annual return.

What concerns me most about this example is that so many people would occasionally check their account and think, “ok, that looks alright” and never know how much they missed.

6.5% annual return doesn’t sound bad…but was it good? No.

Why? Let’s look at an alternative. Morningstar categorizes Baron Growth fund as a “mid-cap growth fund”. What if you’d simply bought a mid-cap growth index fund?

If you’d invested in the iShares S&P Mid-Cap 400 Growth ETF, you’d have $240,455, $52,741 more than you got with the Baron Growth Fund over the same time period:

No need to miss out on $52,741 in exchange for a fancy conference each year. You could buy some very nice tickets yourself with more than an extra ~$5,000+ per year: multiple best-seats-in-the-house Hamilton tickets! Or you could treat 75 – 175 of your closest friends to that same comedian's performance – his recent tickets at Madison Square Garden were $30-$70!)

Or perhaps spend that money on something else: your own retirement, a child’s college expenses, or a charitable contribution that really makes a difference for someone who needs it.

The analysis is the same regardless of what time period you look at – if you invested 1 year ago, 3 years or 5 years. Over each time period, you’d come out behind.

The problem is not limited to funds making the news with splashy events.

There is a role to play for active management, but fees should be:

- Transparent, and

- Reasonable

What makes a fee "reasonable"? For starters, the person paying it knows what it is (back to #1 -- transparent) and feels it is reasonable.

How this applies to insurance

Here at AboveBoard, we are an independent insurance brokerage committed to providing smart and ethical insurance advice.

Some of the permanent policies we broker include the ability to choose how the money in the policy is invested. In general, we favor low-cost, passive strategies as a baseline. But we also see the valid, useful role of active management, particularly in certain asset classes and when it is available to you at a reasonable price.

In all cases, we believe in the principal of informed consent: you should know what is happening with your money, and agree to a strategy because you understand it and feel good about it.

To learn more about our work with permanent insurance policies (e.g. whole life, universal life, variable life, etc.) visit our Private Client page. If you are ready to get started exploring your options, get a life insurance quote or send us a message.